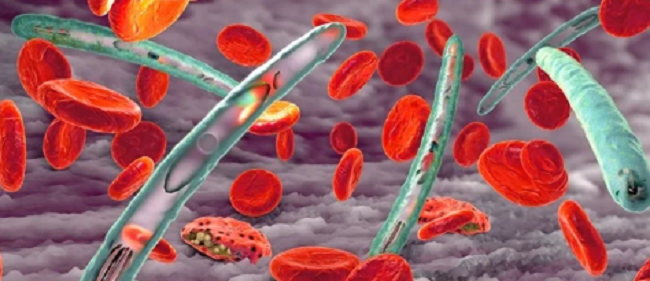

Cerebral malaria is one of the most severe and dangerous forms of malaria, and it is potentially fatal. Now, researchers have justified the use of Khaya grandifoliola for its treatment by traditional healers.

In a new study, researchers found that it can significantly reduce malaria parasites under laboratory conditions. Also, its ethanol extract had a dose-dependent suppressive effect with 78.12percent, 75.30percent, and 68.69percent at doses of 500 mg/kg, 250 mg/kg, and 125 mg/kg, respectively.

Khaya grandifoliola, also called African mahogany, is used as an anti-malarial herbal remedy. The bark and seeds of Khaya grandifoliola are the most common parts used for treatment and are extracted by infusion or decoction.

In this study aimed at evaluating the antimalarial activity of K. grandifoliola stem bark ethanol extract to justify its traditional usage, researchers found that it was able to reduce and inhibit the development of P. berghei, responsible for the destruction of red blood cells during malaria episodes.

Thirty mice out of 36 were infected with malaria parasites and then randomly divided into five groups of six mice each. The remaining six nonparasitized mice formed the normal group. Three hours after infecting the animals, the mice were treated for four consecutive days.

Seventy-two hours after inoculation, extracts at different doses were administered to the mice for 4 days. The level of malaria parasites in all experimental groups was evaluated from the 4th to the 10th days. The mean survival rate was also calculated.

The researchers in the Journal of Parasitology Research explained that the efficacy of K. grandifoliola in the treatment of cerebral malaria could be explained by the chemical constituents of its root extract, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, tannins, saponins, and anthraquinons, which are known to have antiplasmodial activity.

According to them, the suppressive activity of the K. grandifoliola extract is thought to be due to the accumulation of these chemical constituents during the three days of treatment in the animals’ blood, in particular, the alkaloids, which inhibit parasite protein synthesis, and the flavonoids, which bind themselves to the parasite, thus inhibiting parasite multiplication.

“The reduction of the parasite during the curative test in the treated groups could be justified by the presence of terpenoids, in particular deacytlkhivorin in K. grandifoliola, which acts on all stages of Plasmodium development,” they added.

The researchers, however, said that more studies on the extract of Khaya grandifoliola stem bark are required to determine its safety.

Previously, scientists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore and the National Institute of Immunology in New Delhi also declared that turmeric could hold the clue to a cure for cerebral malaria.

They report a complete cure for cerebral malaria in experimental mice with a therapy that includes curcumin, the yellow component isolated from turmeric (Curcuma longa), widely used in cuisine.

The researchers found that “arteether-curcumin (AC) combination therapy, even after the onset of symptoms, provided a complete cure in experimental mice with cerebral malaria.”

According to the researchers, migration of T lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell that plays a central role in cell-mediated immunity) and falciparum parasite-infected red blood cells (pRBCs) into the brain are both necessary to precipitate the disease.

The researchers designed two modules: first, to study the effect of curcumin alone before the onset of symptoms in mice with cerebral malaria, and second, to study the effect of AC treatment after the onset of symptoms.

The study, they say, provides “experimental evidence for the first time” that curcumin alone was able to eliminate the symptoms of cerebral malaria and delay the death of mice by 15–20 days.

While the AC combination therapy given even after the onset of symptoms provided a complete cure by counteracting all the changes characteristic of cerebral malaria and preventing parasite buildup in the blood, the curcumin-treated animals did not show neurological symptoms; they eventually died of anaemia due to parasite buildup in the blood.

They stated that curcumin is an “ideal adjunct drug to prevent and treat cerebral malaria” in humans when a single suboptimal dose of arteether and three oral doses of curcumin are used.

Also, in an edition of PNAS, researchers at McGill University showed that rocaglates, a class of naturally derived products from plants of the Aglaia species, effectively block blood-stage parasite replication in several mouse models and infected human red blood cells.

Importantly, the researchers showed that these products inhibited neurological inflammation and increased survival, including in drug-resistant isolates, highlighting the strong potential of this class of compounds to treat complicated malaria cases in humans.

With pregnant women and children most vulnerable to infection, complications including anaemia and cerebral malaria, the most severe neurological complications from malaria, are responsible for approximately 25percent of the infant mortality rate in some regions of Africa.

Uncomplicated clinical malaria is treatable with antimalarial drugs, but treatment options for cerebral malaria are few, and those that do exist are limited in their effectiveness, a problem compounded by the emergence of resistance in the parasites.

Read Also: 10 foods to avoid if you want to live long