In this feature, VICTOR AYENI uncovers the chilling realities faced by men and women held captive by kidnappers—surviving relentless threats of death, brutal beatings, and horrifying sexual violence. These harrowing ordeals have taken a devastating toll on their mental health and, in some tragic cases, pushed them to the brink of despair

On the evening of May 30, 2023, the serene atmosphere at Kayode Ogunsade’s farm in Sagamu, Ogun State, was shattered by a rapid burst of gunfire.

The once peaceful surroundings echoed with the sharp, jarring cracks of gunshots that sent birds scattering into the dusky sky and leaving Ogunsade and others nearby paralysed with fear.

For a fleeting moment, the electrical engineer dismissed the unnerving sounds as the distant rumble of stone blasting from a nearby quarry or the echo of equipment boring into the earth for water.

But the intensity and proximity of the gunfire quickly erased any doubt; this was something far more sinister.

Ogunsade, an Ekiti indigene, had no intention of being at work that fateful evening. Yet, duty had called, pulling him back to the farm to address an urgent issue—a malfunctioning egg-handling machine critical to the company’s operations.

Little did he know that this routine repair job would place him at the edge of a nightmare.

Uncertain about the source of the loud noises, Ogunsade’s mechanical assistant, a young man known simply as Samuel, cautiously offered to investigate.

With fear etched on his face, he stepped outside the office, the air thick with tension. Moments stretched into eternity as the others waited, ears straining for any sign of trouble.

When Samuel finally returned, his expression was a chilling mix of fear and urgency.

“They’re here,” he whispered, his voice trembling. “Armed men… AK-47s… hooded. They’re at the office.”

His words hit like a thunderclap, shattering any remaining semblance of calm. Ogunsade’s heart sank further as Samuel revealed the grim reality: the attackers weren’t alone.

They had corralled 19 maintenance workers into the farm’s office—workers who had already borne the scars of terror, having fled their northern homes in search of safety, only to be ensnared in yet another nightmare.

Panic engulfed Ogunsade’s team as they scrambled to escape the bandits, prying open the burglar-proof bars on his office window and leaping one by one into the nearby bush.

Behind them, the terrifying sound of the bandits breaking down the office door grew louder, pushing them to act faster.

“It was Samuel’s turn and mine when the door finally gave way,” Ogunsade recalled grimly. “They burst in, guns raised, and ordered us to move. By then, they had already ransacked the other offices, seizing all laptops and phones.”

The bandits, ruthless and efficient, dragged Ogunsade and Samuel out of the building.

Despite the danger, Samuel made a desperate attempt to reason with them in Hausa.

“He pleaded, but the man they called Magaji—the leader, as I later discovered—pulled the trigger. He shot Samuel at point-blank range,” Ogunsade said, his voice heavy with sorrow. “Samuel fell instantly. I found out later he died on the spot.”

His ordeal continued as a teenage Fulani boy, referred to as Yaro, charged at him with a piece of wood.

“He struck me on the head,” Ogunsade recounted, his voice faltering. “The blow tore through my scalp, and blood gushed out uncontrollably.”

The harrowing incident reflects a broader crisis documented by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect.

Since 2011, violence between herding and farming communities—fuelled by competition over scarce resources—has intensified in Central and North-West Nigeria.

This friction has given rise to armed groups, including notorious “bandits,” who have unleashed widespread atrocities such as murder, rape, kidnapping, organised cattle rustling, and plunder.

‘I was almost killed’

At the entrance gate of Ogunsade’s farm, the bandits intercepted a building contractor and his assistant in their car.

Without hesitation, they dragged the contractor out and shot him in the stomach, leaving him bleeding on the ground, while abducting his assistant along with Ogunsade.

The captives were marched through a bush path to a secluded, fenced farmhouse hidden deep in the woods, where they were forced to spend the night.

“Six of us were ordered to lie on the floor,” Ogunsade recounted. “We endured relentless beatings and gunbutt hits. They asked if I was the manager, and I told them I wasn’t, that I was just a maintenance man.”

The bandit leader, his voice sharp with authority, summoned Ogunsade. “Call your oga patapata for the company,” he barked.

Struggling to stay composed, Ogunsade replied, “I can’t remember any phone numbers right now. If you give me either my small phone or one of my SIM cards, I can find the contact details.”

They handed him his phone, and fortune intervened. A month-old message he had sent to his assistant, Ridwan, contained a saved number. Quickly, he told Ridwan, “Please inform my wife and the chairman to contact the kidnappers on this number. Also, send me my wife’s and the chairman’s numbers.”

Before Ogunsade could finish his sentence, a ferocious slap from one of the bandits reopened the gash on his head. Pain radiated through his skull as the phone was knocked from his hand.

Later that morning, Ogunsade’s wife managed to call the bandits. Her voice trembled with tears, pleading for her husband’s safety.

Unmoved by her desperation, the kidnappers coldly demanded a ransom of N30m for the electrical engineer’s release.

Cruel beatings

Describing his harrowing ordeal in the kidnappers’ den, Ogunsade recounted, “We trekked for two hours through the dense forest towards Omu village along Papalanto. Throughout the journey, they beat us mercilessly with wood and gun butts. I fainted twice.

“I remember lying on the ground for about 30 minutes, helpless, as soldier ants bit into my skin. I didn’t have the strength to move. At one point, I heard the distinct sound of a gun being cocked and their leader speaking in a language I couldn’t understand. I thought it was the end for me.”

Ogunsade and the other captives endured six gruelling days in captivity.

Eventually, on June 4, 2023, the N30m ransom was paid to the bandits, and he was released. But his life was irreversibly altered by the experience.

“It was a deeply traumatic experience,” he told Saturday PUNCH. “I spent several days in the hospital, and even now, my right leg hasn’t fully healed. I had to resign from work to focus on my recovery, and I’m still in the process of healing—physically and emotionally.”

During a phone interview with Saturday PUNCH, a medical laboratory scientist, Collins Okoye, recounted the harrowing experience of his uncle, aunt and cousin who were kidnapped in December 2023.

According to him, the elderly couple and their son were traveling from the airport to Owerri, Imo State, when their car was intercepted by armed men at Isiokpo, in the Ikwerre Local Government Area of Rivers State.

“My cousin told us that those guys were armed with guns, shooting sporadically and stopping them and other vehicles,” Okoye explained. “At that point, he had to stop. The gunmen dragged them from the Highlander Jeep he was driving into a nearby bush. The jeep was left steaming with its doors open.”

Okoye noted that the gunfire drew the attention of the local vigilance group, who searched the area for the kidnappers but were unable to locate them.

While in captivity, the victims, including Okoye’s family, were subjected to beatings from the kidnappers, who used the butt of their guns as weapons. His cousin and a few others were released temporarily to collect ransom money demanded by the abductors.

“The experience was traumatic,” he said. “My uncle and his wife were released three days after my cousin was freed after paying a ransom. We had to conduct some lab tests on my uncle because he is diabetic. They were sleeping inside the bush with all manner of insects biting them.”

Okoye added that the captives were separated and poorly fed during their ordeal. “He was separated from his wife while in captivity. They were being served half plate of rice daily. I don’t wish such an ordeal in my enemy.”

Kidnappers’ paradise

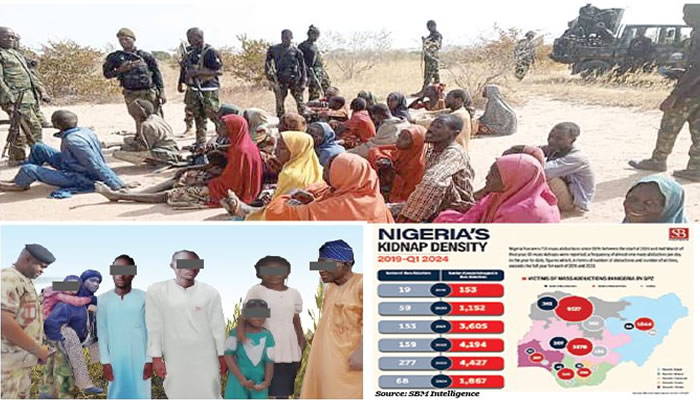

Saturday PUNCH has revealed that bandits and killer herdsmen carry out both random and systematic mass kidnappings on farmsteads, highways, and communities across Nigeria.

The targets of these groups range from high-value individuals, such as current or former government officials and their families, to everyday road travellers, farmers, women, and children.

In the northern regions, Islamic insurgents like Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province are also notorious for executing targeted and random kidnappings.

Meanwhile, the oil-rich Niger Delta, one of the most environmentally degraded areas in the world, harbours armed groups, who have turned to kidnapping as a method of advancing their causes.

These groups evolved from militant organisations in the 1990s that sought to pressure the government into addressing issues like oil pollution and the crippling poverty resulting from destroyed farmlands.

“Kidnapping has become a lucrative enterprise in Nigeria,” a sociologist, Godwin Uwem, told Saturday PUNCH. “In many cases, it involves the collusion of highly placed individuals in society.

“Who knows if these criminals are funnelling their ill-gotten gains to the very people meant to uphold the law? These kidnappers are monsters, and the law must deal with them decisively.”

Abducted in Lagos, found in Ogun

Last year, a Lagos-based furniture maker, Samuel Omoosumi, popularly known as Toby Woods, shared his harrowing experience at the hands of kidnappers.

Omoosumi, who lived with his elder brother, went missing on February 7. Concerned family members reported his disappearance in the Gbagada area of Lagos State.

In a series of tweets on his X account, Omoosumi narrated how he left home to purchase materials for his furniture work in Mushin but decided to first visit Ikeja to fix his phone’s faulty charging port.

“I entered a bus at Oshodi heading to Ikeja. The bus had other passengers, but a few minutes into the journey, I began to feel unusually weak. I assumed it was because I hadn’t eaten all day,” he wrote.

“That was the last thing I remembered. When I woke up, I was tied up and blindfolded. I could hear voices around me but couldn’t tell how many people were there because my face was covered. They took us one by one to another room where they accessed our phones before returning us to the first room,” he recounted.

He further explained that people in the room began disappearing, taken out one by one, never to return.

“At that point, I was terrified. I thought it was the end. When it was my turn, I felt the same weakness I experienced on the bus. The next thing I knew, I woke up in the middle of nowhere, with blood on my clothes and cuts on my body,” Omoosumi revealed.

He described how he stumbled upon a house where an elderly woman took pity on him. “God led me to her. She didn’t speak much, but she saw my condition, gave me water, offered me slippers, and directed me to the road.”

Omoosumi also recounted how disoriented he was during the ordeal. “I had no sense of time or how long I was missing because my face was covered the entire time,” he added.

“I stopped the first person I saw, and he helped me, telling me I was in Ogun State. He assisted me in finding my way back to Lagos, and I boarded a bus heading to Oshodi. A stranger even paid my fare and gave me some money after I shared my story. I also tried calling a number I could remember, but the call didn’t go through. I slept throughout the journey, and by the time I reached Oshodi, I knew I was finally safe.”

Fatal ransoms

The latest Crime Experience and Security Perception Survey, released by the National Bureau of Statistics in December 2024, revealed that Nigerians paid a staggering N2.3tn in ransom to kidnappers over the past year. According to the NBS, 65 per cent of households affected by kidnapping incidents resorted to paying ransoms to secure the release of their loved ones, with an average payment of N2.67m per household.

However, not everyone who paid ransom was fortunate enough to see a loved one return home.

Mental health practitioner Vincent Obinna shared his terrifying experience when he was kidnapped by bandits while travelling out of Sokoto State in 2021.

“I was in their captivity for three days and 18 hours,” Obinna recounted. “They allowed me to make phone calls to raise funds, but everything I said was closely monitored. They would hold my phone, I would give them a number, and they’d call it, only allowing me to ask for money, nothing else. The bandits took everything I had saved just to get out. I even had to borrow more to afford the ransom. To this day, I’m still in debt because of it.”

Obinna’s nightmare escalated when, on the second day of his abduction, two siblings were killed by the bandits for failing to raise the required ransom.

“This experience traumatised me so deeply that I had to leave my job. To this day, I still feel immense fear whenever I travel. It gives me severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Nobody should ever have to experience something like that,” he added, his voice tinged with sadness.

James Obok, a resident of Cross River, shared a similarly heartbreaking story about his cousin, who was kidnapped in Niger State in 2022.

“They demanded a ransom of N50m, and we struggled to raise N15m, but sadly, he was killed,” Obok said, his voice heavy with grief. “The thought of it still haunts me to this day.”

A lawyer, Mazi Thanos, took to X.com (formerly Twitter) to share his pain, writing, “One of my relatives was kidnapped and decapitated even after the ransom was paid. I don’t understand why Ned Nwoko’s gun bill was not approved. I still feel so conflicted every time I see his wife and son.”

A 2023 report by SBM Intelligence estimated that gunmen kidnapped at least 3,620 people across Nigeria between July 2022 and June 2023, with ransom demands totalling over N5bn. Of the ransom sum demanded, only N302m was paid, according to the report, citing payments disclosed by victims and their families.

“We believe these numbers could be far higher,” the report noted, explaining that victims’ families and the police often refrain from revealing whether or not a ransom was paid, and when ransom payments are acknowledged, the amounts are rarely disclosed.

On January 2, 2024, the Nigerian Police Force issued a warning to citizens against using social media platforms to crowdfund ransom payments.

In a post on his official X handle, Bright Edafe, the Delta State Police Public Relations Officer, condemned the practice, calling it “criminal.”

“It’s dangerous and should not be encouraged. Let’s stop making kidnapping a thriving and lucrative business in Nigeria. This tweet is deeper than you think. It’s not about dragging me or the Police. We seriously need to discourage this,” he wrote.

Echoing Edafe’s statement, the Force Public Relations Officer, Muyiwa Adejobi, expressed concern that many families of abducted victims do not inform security agencies or involve them in the process.

“They get scared because kidnappers always work on their psyche, ‘Don’t tell security agents, don’t tell the police, if you do, we are going to kill your relations,’” he explained.

“There was even a case where someone resorted to crowdfunding on social media. This will not help us in any way. It is criminal. It is not allowed. It is condemned. Even the Federal Government condemned it. Crowdfunding is not allowed. How can you come on social media and ask people to gather money to rescue victims? It kills our morale; it undermines the system. We should not encourage that. The more we encourage ransom payments, the more it makes that dirty business lucrative,” Adejobi said.

A trail of traumatised victims

Fighting back tears, an interior decorator named Chinenye shared the heartbreaking story of her father’s abduction in 2013, an ordeal that has left him traumatised ever since.

“The whole kidnap was orchestrated by one of his friends, a woman who was his colleague, and a boss of his. They were paid to kill my dad, but by some stroke of luck, they spared him,” she recounted. “He spent 12 days in captivity without food. Each time we asked him what happened, he would just cry. He developed PTSD. We sold our land to send him abroad. He’s not doing well over there, but at least he’s alive.”

On August 22, 2024, pharmacist Pharaoh (MrMekzy_) shared a conversation he had with a man who was kidnapped along with his wife in June. Although the man managed to escape, his wife was not so lucky. She was released a month later, but only after a heavy ransom was paid.

“Since that time till today,” Pharaoh wrote, “his wife hasn’t said a word to anyone, she doesn’t even eat, she just stares into oblivion and has to be heavily sedated before she can sleep. He plans to fly her abroad for treatment and to change her environment. I support the death sentence for kidnappers.”

Another X user, Andrea Chichi, highlighted the devastating psychological toll kidnappings have on victims, especially those who survive only to be haunted by their experiences.

“A pastor friend was kidnapped along with his wife. His wife was repeatedly raped in front of him. They were later released after paying a huge ransom. But that man couldn’t survive the trauma,” she wrote.

Also sharing the harrowing ordeal of his mother, realtor Vincent described how his mother was abducted by insurgents last year in Kogi State.

“After about a month and some weeks, she was released with one eye; she had lost the other one while being tortured. Only those who have been in such a situation can explain what they go through. The trauma they suffer after being released can still be felt and understood by only them,” he wrote.

Raped in captivity

A civil servant, who preferred to remain anonymous under the name Saheed Bello, shared his traumatic experience with Saturday PUNCH, recounting his abduction along the Kogi-Abuja highway in 2021 by gunmen.

Bello was travelling on a bus when the vehicle was intercepted by armed men on the expressway, who fired shots at other cars.

“I still have nightmares of how they pointed a gun at us and even shot one of us, leaving his body behind,” he said, his voice tinged with pain. “I keep seeing the gory sight of him bleeding on the floor of the bush where we were herded like animals.”

The ordeal was further compounded by the brutal treatment of the passengers. “The men among us were beaten, and the women, including elderly women, were raped by all the gang members—about nine of them—whenever they felt like it. It was terrible. I don’t like to talk about it because it makes me to be triggered,” Bello revealed, his voice quivering with emotion.

A medical doctor, Rita Olowookere (not her real name), shared a heartbreaking account with Saturday PUNCH, revealing that one of her patients, who had been kidnapped in 2023, confided in her about the harrowing experiences of female hostages.

“I know a patient who was kidnapped sometime last year. He recounted what happened while he was in captivity, tears streaming down his face,” she said. “I didn’t even realise when I started crying too as he spoke about the daily rape of the female hostages. He said he wished they had died instead.”

Olowookere continued to share another chilling story. She said, “I know of a family travelling from Akwa Ibom who was kidnapped by terrorists in Kaduna. They raped the women and slit the throat of one man among them. He later woke up in a pool of his own blood to tell the story. These people may be going about their business now, but you can see all over them that they’re not okay.”

An X user, Archlegion (Archlegion89), also weighed in, adding, “I know of a family travelling from Akwa Ibom who was kidnapped in Kaduna. The women were raped, and one man had his throat slit. He woke up later in a pool of blood to recount the incident. These people are walking around now, but you can see that they’re not okay.”

Dankat, a resident from Plateau State, shared a disturbing account from a recent kidnapping incident involving his friend.

“Men and boys weren’t spared from rape by these Fulani criminals from Chad, Niger, Mauritania, and Burkina Faso. Many are still in captivity today,” he said in a quiet voice.

“One man watched them rape his elderly mother, and when they were released, he committed suicide.”

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the security situation in Nigeria has escalated into a humanitarian emergency, with over 8.3m people—approximately 80 per cent of whom are women and children—requiring urgent assistance.

Research by Human Rights Watch has revealed that Boko Haram frequently abducts women and girls from their homes, school dormitories, or streets during attacks on their communities or while targeting passengers in buses.

In a Zoom video shared on X and viewed by our correspondent, a Hausa woman tearfully recounted her harrowing experience of being kidnapped by insurgents. Speaking emotionally with another woman in Hausa, she explained, “When I was in captivity, I saw horror. I still have bad nightmares. That’s why I left Nigeria; that’s why I am here (abroad). You can’t understand what a lot of us who have been in captivity have been through. You won’t know the pain.

“We’ve been raped multiple times by terrorists. You can’t know the agony. Nobody cared. Nobody believed me, nobody said anything or helped me. No one! And that’s what’s happening right now to our children. They are being killed, and nobody is saying anything. I am angry.”

Weeping hysterically, she continued, “I was raped! I was raped by terrorists. I still have marks on my arms. I know what’s going on; I know the pain.”

“The trauma of being raped can be shattering,” said psychologist Bunmi Onipede. “It can leave survivors feeling scared, ashamed, and isolated. They may suffer from flashbacks, nightmares, and other painful memories of the attack.

“Being kidnapped can lead to PTSD, depression, and other forms of anxiety. What victims need is therapy. It’s time we establish trauma recovery centres in Nigeria where citizens can access professional therapy and counselling to overcome their experiences. These centres should also be made affordable.”