On October 22, Wale Edun, finance minister and coordinating minister of the economy, told investors in Washington DC that Nigeria needed to raise oil production to address foreign exchange (FX) supply issues.

“The key thing about the foreign exchange market is really supply. We just need to get our oil production up [and] that will deal with the issue of foreign exchange supply and pressure on foreign exchange every time there are large flows,” Edun said, while taking tough questions about Nigeria’s economy at the World Bank/IMF Meetings in Washington D.C on Tuesday.

As the country’s currency, the naira, falters, losing nearly a third of its value since the Bola Tinubu government stopped artificially propping its value, crude oil can provide the much-needed supply that will lift the naira.

Data sources from FMDQ show the naira strengthened against the U.S. dollar on Thursday, October 24, 2024, closing at N1,601/$1, marking a three percent appreciation from N1,651/$1 recorded the previous day.

The Tinubu government has ambitions to raise output to two million barrels per day, but bottlenecks like sloppy approvals for International Oil Companies (IOCs’) divestment, declining oil rigs, idle oil assets and under-investment have proven to be elephants in the room.

Read also: Nigeria needs high oil production to alleviate FX pressure, says Edun

Sloppy approvals for IOC’s divestment

Traditional oil and gas firms from ExxonMobil to Shell that have flocked into Nigeria for its oil are gradually pulling back on account of insecurity or the allure of other markets with better fiscal terms than Nigeria.

Divestments by oil majors used to provide local operators an opportunity to prove their mettle, taking declining fields’ past production peaks and improving host community relations to deliver higher royalties to the government. Now, Nigeria is scrambling to extract value from divested fields.

BusinessDay’s findings showed Nigeria’s decision this week to block Shell’s $2.4 billion sale of its onshore assets has sent a negative signal to investors.

The Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) did not give reasons for its decision and Shell is yet to comment. The company has ties that stretch back to more than half a century and is one of the biggest investors in Nigeria’s oil, which is the backbone of the economy and biggest foreign currency earner.

A similar deal by Exxon Mobil to sell onshore assets to Seplat Energy was approved this week, but only after a wait of more than two and half years.

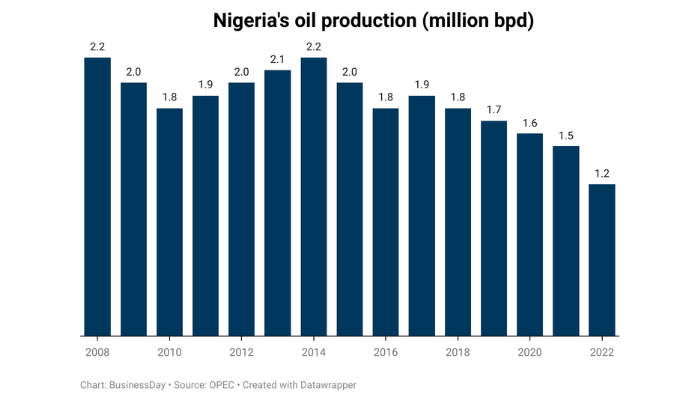

The net effect of this development is worsening output in Nigeria’s oil production.

On October 14, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) said Nigeria’s average daily crude oil production dropped to 1.32 million barrels per day (bpd) in September 2024.

Yet, representatives of local oil companies said they are capable of boosting Nigerian output by 200,000 bpd within two years if the government can speed up the approvals of the deals.

“We strongly advocate that our member companies – Seplat, the Renaissance Consortium and Oando – have the proven track record to successfully take over and manage these onshore and shallow water assets,” Abdulrazaq Isa, the Independent Petroleum Producers Group, said at an industry event.

Read also: Nigeria’s oil output falls by 40,000 bpd as OPEC struggles- Reuters report

Declining oil rigs

The latest data from OPEC on Nigeria’s oil rig count from January to October 2024 show fluctuations in the level of exploration, development, and production activities in the country’s oil and gas sector.

The count started at 17 rigs in first quarter (Q1) and second quarter (Q2) of 2024, before dropping to 14 in the third quarter (Q3) of 2024.

“Nigeria, a previous bright spot-on big oil and gas investors’ radar screens, has dimmed substantially as investor attention is increasingly drawn to new and emerging developments in Namibia, Ivory Coast, Angola and the Republic of Congo,” NJ Ayuk, executive chairperson of the African Energy Chamber, said.

He added, “With two-thirds or more of its revenue coming from oil, investor flight is a serious problem for Nigeria.”

Idle oil assets

Oil receipts fund the country’s budget, but many oil and gas projects lie idle, threatening the target set over a decade ago to raise reserves to 40 billion barrels.

These big-ticket projects include: Zabazaba 150,000 barrels per day (bpd); Shell’s Bonga South West, 225,000bpd; Bonga North project, 100,000 bpd; Chevron Nsiko project,100,000 bpd; Exxonmobil’s Bosi; 140,000 bpd; Satellite Field development phase, 80,000 bpd and Ude 110,000 bpd.

Oil experts surveyed by BusinessDay said Nigeria’s path to economic prosperity may lie in optimising idle assets, a development that will require disciplined planning, economic reforms and consistent government policies that can inspire investor confidence.

“Officials at both regulatory agencies and other agencies still demand bribes to attend to licences and approvals, and the delays in the process and bureaucratic obstacles have not changed,” a senior industry source, who pleaded not to be quoted, said.

Under-investment

When an oil executive said Nigeria needed $25 billion per annum in investments to be able to achieve a production target of two million barrels daily, the task at hand for Nigeria came into better perspective.

The 2010s witnessed a period of significant Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from international companies eager to tap into the country’s vast oil and gas reserves as the future for Nigeria’s nascent indigenous upstream oil and gas industry looked bright, almost dazzlingly so.

In 2014, Nigeria attracted the largest amount of FDI of any African country, with inflows exceeding $22.1 billion. This influx of capital fueled major projects, including deepwater exploration and development of new oil fields.

In Q2 of 2024, oil FDI stood at $5 million.

“Prioritising political interests over transparency and due process in asset sales has led to corruption, mismanagement and, ultimately, the underperformance of the sector,” Austin Avuru, executive chairman of AA Holdings, said at the Harvard Business School (Association of Nigeria) event in Nigeria’s commercial capital.

He noted that those who should manage the process for a smooth transition from oil majors to local operators turned it into an ‘Approval Power Play.’

“Political connections, rather than capacity, became the qualifying criteria, in the absence of guidelines and defined processes,” Avuru explained.