Again in Might, the Russian dissident filmmaker Kirill Serebrennikov returned to the Cannes Movie Pageant in individual for the primary time since his debut look in 2016: within the interim, he had spent virtually two years beneath home arrest in Moscow, resulting from doubtful fraud expenses laid – and just lately rescinded – by the Putin regime. He introduced with him a brand new interval drama in regards to the disastrous marriage between the Russian composer and Antonina Miliukova, whose fan-like adoration of her husband curdles into vengeful obsession. (Their union was additionally the topic of Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers.) The sticking level is Pyotr Ilyich’s homosexuality, which he gained’t talk about, and he or she gained’t acknowledge.

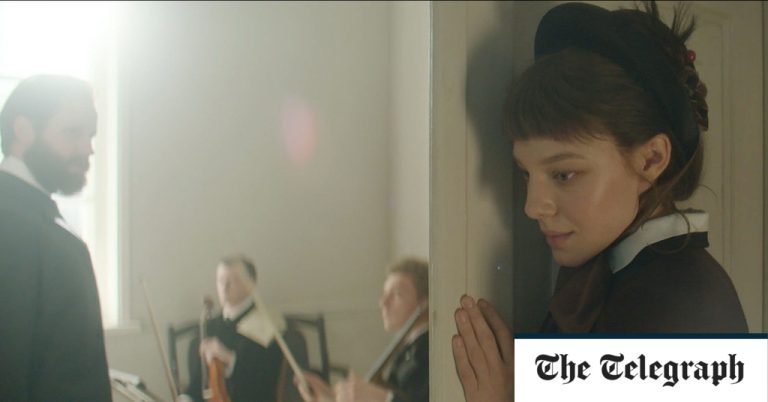

The 2 spend evenings at louche salons the place the petit-bourgeois Antonina (intensely performed by Alyona Mikhailova) doesn’t suppose to query the presence of such anatomically frank artworks on the partitions, or why all the opposite visitors occur to be males, or why they’re dancing so carefully with one another, a few of them in make-up and drag.

A lot as it could be good to report that the movie lived as much as its director’s triumphant return, it’s sadly a swaggering chore: watching it appears like competing in a form of art-house cinema Krypton Issue, with a barrage of interpretative dance interludes, unflinching full-frontal male nudity, pulverisingly bleak mise-en-scene, and writhing psychological collapse. (The truth is, one Tremendous Spherical scene in direction of the top by some means manages to mix the entire above.)

There’s a punchy setting-out-the-stall sequence at first although, the place Antonina arrives at her husband’s funeral in 1893, just for his corpse to climb out of the coffin and begin berating her from the afterlife. “What was the purpose of this vulgar tragicomedy?” he rants, snowy beard bristling with vitriol. (In each loss of life and life, Tchaikovsky is performed by Odin Lund Biron.) Two hours and 25 minutes later, the viewer might discover themselves pondering the identical query.

Flashing again to 1872, we discover Tchaikovsky already a rising star of the Russian classical scene, and Antonina a smitten scholar, determined to make his private acquaintance. She buys a information to writing love letters, tracks down his private handle, and convinces him to go to her in her modest rooms, that are scrubbed beforehand to a Hammershøi-esque spartan gleam. A squirmingingly awkward reverse proposal takes place, which he politely but firmly rebuffs, solely to alter his tune later for causes the movie by no means fairly dramatically unpicks.

The early phases of their relationship are like a reverse in-joke – everybody who encounters the couple appears to be stifling a chuckle at poor Antonina’s obliviousness – till Pyotr merely goes off on a visit and by no means returns. A divorce is dangled by way of his pal, the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein (Miron Fedorov), however Antonina turns it down on a degree of precept, and her descent into insanity – introduced on by a cocktail of romantic self-delusion and the overall intractability of late-Nineteenth century Russian patriarchy – swiftly follows.

Stylistically the movie follows swimsuit, with intricate single-take scenes that elide complete days in a single digital camera swish. However the impact is much less immersive than gruelling, and leaves this breakdown movie unworkably psychologically opaque.

In cinemas from Dec 29