Nigeria’s dream of a domestically-produced aluminium industry appears further out of reach as the $3.2 billion Aluminium Smelter Company of Nigeria (ALSCON) in Ikot Abasi, Akwa Ibom State, misses yet another deadline for its much-anticipated revival.

ALSCON was established purposely to utilise and enhance Nigeria’s huge gas reserves and to discourage gas flaring, which could be rechanneled to generate electricity for the smelter plant via a gas-to-power model.

The smelter, which was commissioned in 1999 but has been idle since 2007, was initially expected to resume operations in 2020, but that deadline was pushed back to 2023, and now, it appears unlikely to meet even that revised target.

The project has been plagued by delays, funding shortfalls, and contractual disputes for over two decades, with the latest missed deadline being the last quarter of 2023.

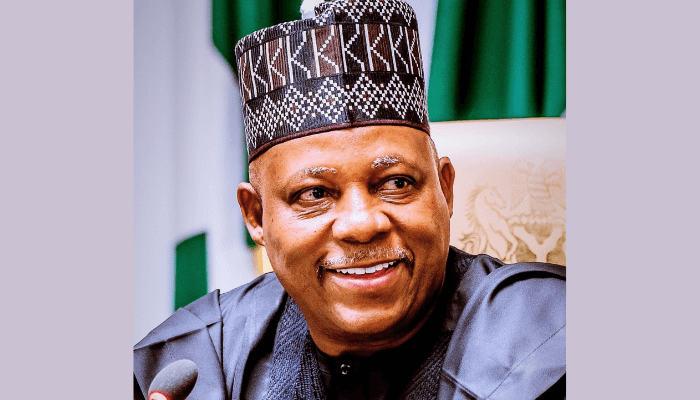

Kashim Shettima, Nigeria’s vice president had promised the plant will come on stream by the last quarter of 2023 while speaking at a meeting with the management of Russian Aluminium Company – UC Rusal (one of the partners of the project) and other stakeholders in the project on the sideline at last year’s Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg,

“The sooner we get this plant back to production, the better for everyone. We need to walk the talk; the Nigerian people deserve better,” Shettima said last July.

At the same event, Gabriel Aduda, permanent secretary political and economic affairs office, office of the secretary to the government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, told BusinessDay that agreements had been signed with Rusal (UC Rusal) to revive the plant.

“We are left with refining the financial obligation with UC to revive the project,” he said. “The plant should be ready in the last quarter of the year (2023).”

This latest setback has reignited criticism of the project, with many Nigerians questioning its viability and economic benefits.

Critics point to the project’s ballooning costs, missed deadlines, and lack of transparency as evidence of mismanagement and poor planning.

“It’s a national embarrassment,” said John Oboh, an economist based in Lagos. “This project has been going on for nearly 30 years, and we still have nothing to show for it. The government needs to come clean and tell us what’s really going on and whether this project is ever going to be completed.”

Rusal acknowledged the discussions but refrained from offering additional specifics. It held an 85 percent stake in the plant, with the Nigerian government possessing the remaining share.

BusinessDay reached out to Rusal on two different occasions via email for comment on the development of their agreement with the FG but did not get a response at the time of publication.

The origin of this saga can be traced back to a legal wrangle concerning the ownership of the plant, spanning numerous years and traversing various legal corridors before reaching the pinnacle of judicial authority.

The initial shareholders were: the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) and the Ferrostaal of Germany with a 70 percent and 30 percent shareholding ratio respectively. Subsequently Reynolds Incorporated acquired 10 percent of Ferrostaal’s shareholding in ALSCON. Consequently, the shareholding structure became FGN (70%), Ferrostaal (20%), and Reynolds (10%).

BusinessDay’s findings showed ALSCON commenced operations on October 15, 1997 but had to cease production on 6th June 1999 due to the withdrawal of Reynolds, the technical partner, because of irreconcilable differences between Ferrostaal and Reynolds, inadequate working capital, insufficient gas supply, and lack of dredging of the Imo River to facilitate the importation of raw materials and exportation of aluminium ingots (finished product).

The dispute sprouted from the privatisation initiative of ALSCON, wherein BFIGroup, a consortium of Nigerian and American interests, emerged victorious in the bidding process in 2004.

However, the BPE invalidated BFIGroup’s bid, instigating a protracted legal contest. In a ruling in 2012, the Supreme Court affirmed BFIGroup as the rightful bidder for ALSCON, mandating the company’s transfer to the consortium.

Despite the Supreme Court’s directive, the BPE, under Okoh’s stewardship, failed to comply. This defiance prompted BFIGroup to seek enforcement of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Federal High Court in Abuja.

On December 17, 2019, Justice Anwuri Chikere presiding over the Federal High Court decreed Okoh’s imprisonment for at least 30 days due to his disregard of the Supreme Court’s mandate.

Subsequently, Okoh and the BPE appealed with the Federal Court of Appeal, seeking a halt to the execution of the High Court’s judgment. However, after two years, the Appeal Court found their appeal devoid of merit, thereby upholding the Federal High Court’s decision.

“The privatisation process for ALSCON was poorly done. A lot of privatised government entities have underperformed. There must be repercussions for poor decisions taken by Government officials, which affect the economy and our people,” Eze Odiri, a public sector consultant, said.

Talking about the impact of this on investment flow into Nigeria, Odiri, said “True and genuine investors will not come to Nigeria with non-transparent processes. That will continue to leave us with people without the capacity to run our assets aground. It’s a pitiful situation.”