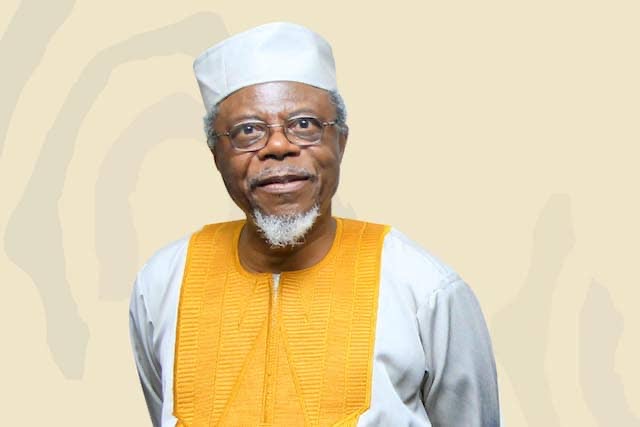

For professor of African history, Toyin Falola and othereminent scholars in indigenous African languages and literatures, it had become very expedient for Africans to utilize the full potential of the continent’s indigenous languages and literatures for growth both locally and at the global stage.

Falola while chairing a penal of foremost linguists at the last edition of the Toyin Falola Interview Series with the theme: ‘Languages and Archives in Knowledge Production About Africa’, noted the contributions of Ahmed Bamba and other indigenous African warriors, clerics and scholars in foregrounding the relevance of identity construction via language. Members of the panel included Ghirmai Negash, professor of English and African literature and also the Director of the African Studies Program in Ohio University, he also founded and chaired the Department of Eritrean Languages and Literature at the University of Asmara; Ngom Fallou, professor of Anthropology and former Director of the African Studies Centre at Boston University, with research interest in the interaction of African and non-African languages; Abiodun Salawu, professor of Journalism, Communication and Media Studies, and Director of the research entity: Indigenous Language Media in Africa (ILMA) at the North-West University, South Africa; Ousseina Alidou, a distinguished professor of Humane Letters in the School of Arts and Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick; and John Mugane, professor of African Languages and Cultures at Harvard University and the Director of the African Language Program.

According to Falola, “I’ve been interested in what I called the cultural policies of some warriors and missionaries of the 19th century. They did not use the word cultural policy, I framed it as such. I have been trying to understand Chaka Zulu, Ahmad Bamba and Dan Fodio. So what we now call Zulu identity emerged from some of the cultural policies of Chaka. And you see how that Zulu identity remains influential in South Africa although the Zulu are 17 per cent of the population. When I turn to Fodio whom I’ve read in translated works, of course, the minority conquered the majority but they adopted the language of the majority. So the Fulani picked Hausa. But when we now go to the area you know best Ahmed Bamba, people don’t know Ahmed Bamba as well as they should do. The young man, one of the most imaginative African writers, wrote far more than anybody both in the 18thand 19th centuries. He did two things both of which are connected to this topic. He said, you can be a Muslim but you don’t have to be an Arab, which is very fundamental. By saying that, he is basically arguing that you can be a Muslim but you can filter out many of Arabic cultures. Bamba said that why don’t you address identity via language instead of ethnicity? And the way he framed his argument is, what do you become if you are able to speak Wolof, Hausa or Yoruba? Perhaps the kind of ethnicity and tensions that emerged would have taken a different turn. I’m not talking about contemporary scholars with PhD, my examples are those who had education via other means.”

Building on Falola’s string of engagement, Professor Ngom noted that ethics has also remained the focal point of African epistemology which Bamba espoused. “Before recently, the assumption is that relevant or good knowledge about Africa is to be found only in European languages. Now we are finding the writings of Ahmed Bamba or the writings of the disciples of Ahmed Bamba on how and why Ahmed Bamba reached such decisions. Ahmed Bamba was born in a very agitated period of colonisation. He learned from history the consequences of Jihad from the region. In fact, one of his family members was affected by this revolt that occurred in the period. His first mission from the archives that I found was to reform Islamic education itself from a book-based memorisation to an ethical form of learning so that he emphasised ethics. And that’s because he realised for himself that society was ill, and the best way to deal with such illness is to train people who are ethical. So it is not just by praying five times a day but it is about being a good person to your neighbour. And he implemented that vision by de-emphasising Arabisation.

“Bamba also experienced the same bigotry that for example, Martin Luther King and all these experienced in the Christian context. He was aware that race was also used in the Muslim world to create hierarchy where black people were at the bottom; he rejected that in one of his first writings. So in terms of pan-African thinking, I think Ahmed Bamba is a key player because he understood that the challenge the black people and Africa in general were facing was a challenge of hegemony. But how do you train people who can survive and flourish? That is why he emphasised language. Bamba was a universalist in many ways because he wanted to continue to engage the Arab world and his colleague Muslims but he told his senior followers who were writing in Arabic to shift and to write in the local languages.

“He thought writing in the local language, conveying his teachings to the masses, could only be done realistically in the local languages. And in so doing, he elevated not only the local languages but also local virtues. One thing I find interesting when you look at these archives is that Bamba was so interested in ethics that he even was a friend of drunkards. What is important is ethics. And I think this is not only unique to Bamba, this is a fundamental African virtue that you find in Hausa land or East Africa. There is the virtue of humanity. We are losing many things when we don’t incorporate these things. That was why I said when these people write, they are not writing because they are Muslims or Christians, they are writing as Africans and they are trying to address the social problems in our communities. Ahmed Bamba is just one example; there are many others. We need to incorporate these voices. These voices have been excluded from our discussions about Africa.”

Emphasising the interconnected relevance of African languages and literatures, Professor Negash argued that “They have functions or roles to play. Literature has benefits in Africa, particularly I think in about texts like Things Fall Apart. It is probably a belated response to Hegel, right. I was saying Hegel considered Africa as cultureless, story-less, civilisation-less, as a boring place. If you look at Things Fall Apart, in Achebe responding to these questions, there is discussion about religion, governance, about very sophisticated kind of negotiating the nuances of gender. I would like also to invoke our great Ngugi from Kenya. He was the one also who gave us this kind of counter-discourse. Well, I just mentioned there are epistemological figures, he is one of the epistemological figures. He gave us the notion of decolonising the mind. He was among the first who started speaking back. Even probably, chronology is always kind of risky, people like the great Palestinian thinker, Edward Said, wrote these major books and interventions, writing back. Ngugi’s writings, theoretical as well literary, made a huge contribution. The role of literature in the production of knowledge is enormous. It is a little unfortunate with language. With the exception of Ethiopia and Eritrea, those countries have very long tradition of writing in their own languages. Probably in some parts of Nigeria, I know that there is literature in Yoruba and other languages, and Swahili of course.

“The attempt, the push, should be using these languages for literally purpose as well. So I would say there is literature in European languages, we are not going to dismiss that, it has played enormous role, it continues to really play a huge role, I’m thinking of people like Adichie who are contributing to the decolonial conversation in the diaspora as well as in the continent. But we also need the local indigenous African languages to be used for literary purposes.”

Earlier in his delivery, Negash elaborated on the formation of epistemology and how they are put to use. For him, “The question of epistemology has a long history. But in its current form as we got it, is mainly from post structuralists. Episteme of course as many us understand is from Greek language. The notion of episteme is a set of relations that unites different discursive practices. This is a quotation from Michel Foucault, I’m using this because he was the one who elaborated on this point. What he meant by ‘unites discursive practices’ includes the statements, the concepts, the constellation of ideas. They generate scientific knowledge across disciplines starting from the humanities, the medical sciences, anthropology, history and what have you. Because of these discursive practices, they have to be repetitive. Narratives are created, statements are created, worldview is created and these become the sciences.

“When we have the scientific disciplines in the scholarships, we usually have also people who carry them so to speak. There are exponents of the theories, of the statements. For example, the idea of post structuralism, the idea of Marxism, or the idea of disciplines in histories, there must be also people who are coming with new ideas. There is also the idea, for example, of creating new paradigms in Linguistics, like Chomsky and so on. These are the people who create discursive practices or discursive formations. Once this is set, there are also underlying subtexts of power relationship at a global level. Then it becomes a dominant, the mainstream idea to which not just academics and scientists and scholars but also the general population listens to: who is this speaking? How should we do this? And so on and so forth.

“So in terms of discursive practices, discursive formations, epistemologies, they are not birthed, but there is always a context. Always a context is created. And the context comes from place to place. And if the context is created in terms of power relations, for example, let me take you back to the major epistemological figure, exponent of a particular set of ideas, a paradigm, I’m taking of Hegel who had the platform to talk about Africa: Africa has no culture, Africa has no civilisation, Africa has no history, Africa has no language, and so on and so forth. Once that idea and epistemology is created, established, and reproduced, and then it comes in different forms. It goes to different disciplines. It goes to linguistics; it goes to history, it influences many methodologies across disciplines.

“There is something very important for us to ask. Where were Africans when these paradigms/discursive practices were created? Africans were producing knowledge; Africans had religion; some of them had even scripts like these classical languages of Eritrea and Ethiopia and other parts of the world. Then there is what we call epistemic violence, art work, the European kind of epistemology was self-perceived superiority towards the other indigenous African knowledge systems. So it was dominating because of colonialism, because of imperialism and this is where the other lap or the connection between colonialism, imperialism and epistemology comes to work.

“If I may add, let’s also be reminded that the knowledge production in terms of global order has been created in between six and eight languages. These are European languages, if you want to add Latin and Greek languages as well. The other languages of participations, African languages particularly, although had presence, were always left on the margins. It is always superseded as if it was not there, because of the power dynamics.”

Professor Falola, however, noted that gender and silence in African formation and transmission of epistemologies have remained very knotty issues. In her reaction, Professor Alidou opined that “Very often, we don’t talk about silence; we are looking for voices and for writing. Once we have silence, it means erasure. It means a lack of connection of the possibilities that existed and the potential that can be offered in the present and in the future. If within the domain epistemology, epistemology is seen only as the monopoly of men then it means that humanity is not progressing the right way. It means that there is a whole body of knowledge system, a thought process that has been dismissed. Epistemologies are not conveyed only through Latinisation or through any script system. Whether it is Ajami, Tiv or Nko, epistemologies are carried through several mode systems and African women have contributed to the production of epistemologies in their indigenous literacy systems, in the oralised forms and other forms of conversations, whether they are the scripts, the embodied forms or other manifestations of ways of carrying through process.

“The Southern African region, the West African region, the Maghrib region and central Africa all have monographs which include important works by women. Women were forward-looking in terms of saying multilingualism is the Lingua Franca in Africa. So if we are talking about modern African literary figures, we cannot escape establishing women as critical in the formation of modern African literature in multilingualism. Women created an inter-lingual dialogue between writing systems in the poetic and literary sense, and also philosophising into that. The cultural policy of the Tuareg people was such that women were the transmitters, the custodians of literacy. However, with the interference of European colonialism in the French system, it was a total linguistic assimilation and dismissal of any indigenous literacy system. It is very important that we decolonise the psychology that comes to be associated with how we understand the history of writing in the multiplicity of the script system of Africa. We have to decolonise the way we write and think and also ways of translating Africa.”

Remarking on the strength of African languages in media communication relevance, Professor Salawu informed the audience that indigenous languages have been proven to be effective for educational and intellectual purposes. According to him, “These languages can be used for different purposes not only in the mass media or digital media. Even for educational purposes, native languages have been proven to be effective. There are a number of studies that have been done about this which points to the fact that people learn better when they are taught in their native languages. The notion that African languages are not adequate to teach technical subjects or science subjects has also been disproved because as Ngugi wa Thiong o said, no language is superior to another. Probably our challenge in Africa is that, because of colonisation, we have not been able to develop our languages very well. And that is why people will say that those languages are not adequate to teach science, even to be used in higher education.

“The fact is that if we intellectualize these languages, they will be used and very effectively for teaching in higher education. So, that to me is the way to go because for instance, if you look at a language like Afrikaans in South Africa, Afrikaans is used very well in higher education. It is used to teach in universities in South Africa. There are a lot of journals published in Afrikaans. And that was because the former apartheid government was able to invest heavily in the development of that language. And I want to believe that even Swahili in East Africa is also to a large extent able to do some of these things we are talking about. So I believe that our languages are adequate enough to do all these things if only we can intellectualize and develop them very well.”

The session which was beamed on several social media platforms had very prominent archivists, linguists and scholars in attendance.