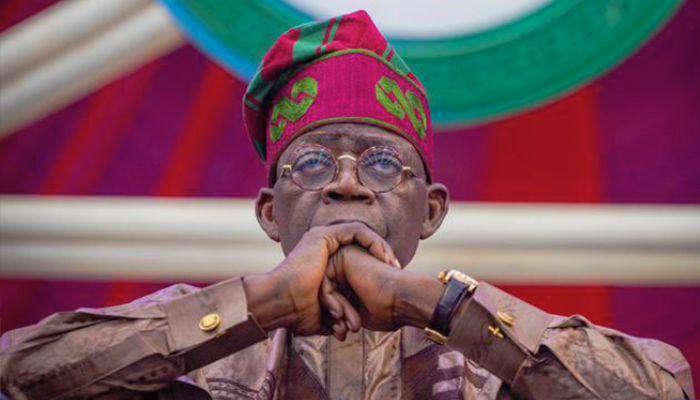

President Bola Tinubu’s effort to shake up the Nigerian economy and boost growth is already stumbling. After succeeding Muhammadu Buhari in late May, he scrapped costly fuel subsidies, removed the central bank governor and overhauled the country’s exchange-rate policies — effectively devaluing the currency, the naira. Tinubu’s initial steps enthused investors but elicited a public backlash over rising food and fuel costs. By mid-September, Tinubu had paused the fuel subsidy phase-out and the naira was in freefall on the informal market, frustrating his efforts to close the gap between the currency’s official and unofficial price.

1. What’s wrong with Nigeria’s economy?

About 40% of Nigeria’s more than 200 million people live in dire poverty, according to the World Bank, with just 11.8% of the labor force involved in wage employment, according to the nation’s statistics agency. Inflation climbed to an 18-year high of almost 26% in August, with food costs growing 29%. Corruption is endemic, many state institutions are dysfunctional and armed bandits and Islamist militants have free rein across swathes of the country’s north. The government spent 96% of the revenue it collected in 2022 on servicing its loans. Oil production — the lifeblood of the economy — has reached lows last seen in the 1980s. In August, Nigeria produced only 1.18 million barrels of crude, nearly 500,000 barrels below its allotted OPEC quota, which it has been unable to meet for at least two years. In June, the World Bank forecast that Nigeria’s gross domestic product would only expand by 2.8% this year, barely keeping pace with the increase in the population, and “far slower than needed to make significant inroads into mitigating extreme poverty.”

2. What’s Tinubu’s plan for turning things around?

His priorities include boosting manufacturing, making electricity and public transport more accessible and affordable, simplifying a complicated exchange rate system and increasing investment in road, rail and port infrastructure. He’s pledged to divert money spent on fuel subsidies — $10 billion in 2022 alone — to improve the health and education system and create jobs. He plans to overhaul the tax system to shift more of the burden to wealthier citizens, and cut corporate taxes. Cheap financing will be provided to 75 manufacturers and 1.1 million small and medium-sized companies to help bolster hiring, while the national minimum wage will be increased. Tinubu has also pledged to recruit more personnel to tackle extremist violence and instability and invest in better military equipment.

3. How’s it all going?

Within days of taking office, Tinubu scrapped the fuel subsidies that had been in place since the 1970s, arguing that they have outlived their usefulness and mainly benefitted a select group of wealthy and politically connected individuals. Pump prices and transport costs surged following the move, triggering public anger. A report by humanitarian organization Mercy Corps illustrated how hard ordinary Nigerians were hit by inflation: It found that food prices jumped by 36% and transport fares by 78% in the northern state of Borno within a week of the fuel subsidy cut, and that hunger and petty theft rose. In mid-July, the government declared a state of emergency, allowing it to take exceptional steps to improve food security and supply. The national power grid collapsed twice in September and a surge in business confidence that greeted Tinubu’s reform push has dissipated.

4. Why did Tinubu remove the central bank governor?

Governor Godwin Emefiele, suspended by Tinubu in June, was blamed for a botched program to replace high-value naira bank notes. He was subsequently detained by the secret police and charged with the illegal possession of a shotgun and ammunition, which was later withdrawn and replaced with a fraud charge. Emefiele has denied wrongdoing and says he is the victim of “a political witch-hunt.” In July, Tinubu ordered a special investigation of central bank operations under Emefiele, whose attempts to manage the naira gave rise to a web of varying exchange rates and drove many businesses and people to the informal market. While the practice was aimed at shoring up the value of the naira and the nation’s foreign reserves, Tinubu said it had made a handful of currency speculators “filthy rich, simply by moving money from one hand to another.” Emefiele also approved billions of dollars of loans to the previous government, helping push public debt to a record.

5. Who else has been sidelined?

Tinubu has also suspended Abdulrasheed Bawa, the head of the nation’s anti-corruption agency, following what he described as “weighty allegations of abuse of office.” The president took almost two months to appoint a cabinet of nearly 50 members, among them some prominent technocrats including Wale Edun, named minister of finance and coordinating minister of the economy. He’s also named new heads of the army, navy, air force and police.

6. What’s happened with the naira?

The central bank in June announced changes to the way the foreign-exchange market operates, saying the naira would trade freely until it finds a new market-related level. Under Emefiele, the bank sold limited amounts of dollars at tightly controlled rates to companies and individuals. Businesses complained that this system made it difficult to operate and deterred investment. Many resorted to using the unofficial market, where the dollar traded more freely but at about a 60% premium to the official rate. After the new currency regime were announced in June, the naira slumped. The central bank intervened in the market to stem further losses, with little success. Three months later, the currency had tumbled to a record low of 1,000 to the dollar on the informal market.

7. What reaction has there been to Tinubu’s changes?

Tinubu won February’s presidential election with just 35.2% of the vote, a relatively weak mandate, and he’s under pressure to show his overhaul of the economy is working for ordinary people. Investors, economists, bankers and multilateral lenders have long called for changes to exchange rate policy and a more orthodox approach by the central bank, and they largely welcomed the measures he announced. Yet many foreign investors appear reluctant to return to Nigeria unless local assets offer bigger returns to make up for the many risks and the currency stabilizes. Local business leaders are concerned a sudden hike in interest rates aimed at defending the naira could stifle economic growth. Investors were offered a glimmer of hope in late September when a former chairman of Citigroup Inc. in Nigeria, Olayemi Cardoso, took over as central bank governor with a pledge to refocus the institution on its “core mandate.”