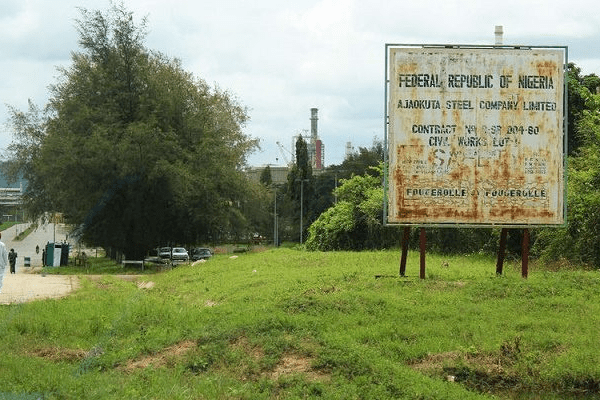

In the face of poor performance and huge overheads, fixing Nigeria’s Ajaokuta Steel Mill has remained the promise of every administration since 1999.

Ajaokuta Steel has been a Nigerian attempt to boost industrialisation in the country for four decades. It was initiated by President Shehu Shagari in 1979. This steel processing plant became a point of reference for subsequent heads of state to make promises and bold statements.

Nigeria’s long history of billion-naira spending on turnaround maintenance has continued with the present government, as Shuaibu Audu, minister of steel development, has announced plans to generate approximately N35 billion for the Ajaokuta Light Steel mill by tapping into the local financial market.

“The precedent is on the Renewed Hope Agenda in which the Minister of Works is driving plans to construct about 30,000 kilometres of roads across Nigeria, where they will need about 7 million metric tonnes of iron rods,” Audu told State House correspondents on January 11.

“We can produce about 400,000 tonnes of those iron rods in Ajaokuta if we’re able to restart the steel plant. The president gave approval for us to raise money locally,” Audu said.

Ajaokuta Steel Mill was designed to be the biggest industrial project in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1970s. It was expected to produce 2.6 million tonnes of steel within the first year, half as plates and the others into structural steel, rods and wires.

Luckily for the country, large iron ore deposits were found in Itakpe, Ajabanoko and Oshokoshoko all in Kogi State. The Ajaokuta Steel Complex and Delta Steel Company were subsequently incorporated in 1979 as limited liability companies.

The expectation was for a doubling of the production capacity immediately after initial operations commenced. In addition, Ajaokuta was to help expose Nigeria’s industrial metallurgy and economy to the in-house manufacturing of capital goods and was billed to create a total of 500,000 jobs, among other economic benefits.

The ultimate goal, said Maxim Matusevich, professor of history at Seton Hall University, was “to serve as Nigeria’s main platform towards becoming an economic and industrialised global power.”

The initial contract for the construction of Ajaokuta, Matusevich noted, was signed on June 4, 1976 for $1 billion, with commercial production scheduled to commence in 1980 or shortly thereafter.

However, the cost, he further observed, was reviewed upward several times before 1985.

“For example, by February 1980, the cost had risen to $12.7 billion (about N7 billion at the time), and it was renegotiated and raised a few times afterwards,” he said.

Between 1980 and 1983, the federal government stated that it had achieved 84 percent completion of the Ajaokuta Steel plant, having completed the light mill section and the wire rod mill.

It was also widely reported that erection work on equipment reached 98 percent completion around 1994. Ever since then, Nigerians have been made to believe that Ajaokuta is 98 percent completed.

For most analysts here lies the biggest puzzle: Why is a company that is 98 percent completed still failing to produce a sheet of steel over 35 years after its establishment?

An on-site Al Jazeera report conducted in 2018 showed that Ajaokuta Steel remained moribund. At the time, the federal government had promised that the steel plant would commence operations in about 18 months (2020).

Sumaila Abdul Akaba, Ajaokuta Steel Company’s administrator, told Al Jazeera that all the plants were in good condition.

“The quality of the plants is still intact. But as of now, what we’ve done is to start to re-engineer the plants, refurbish, and try to make them work,” Akaba said in 2018.

Despite being unproductive, government after government has continued to pump billions into the Ajaokuta project as the latest estimate by BusinessDay showed the colossal project cost Africa’s biggest economy N49 billion.

The project’s long history of decay and wasteful spending on maintenance have triggered an increased feeling of bitterness in the hearts of many Nigerians whenever they hear the government’s intention to pump more money into them.

BusinessDay’s findings showed the federal government budgeted N3.9 billion in 2016 and N4.27 billion in 2017 for the resuscitation of the Ajaokuta Steel Company. It budgeted N4 billion for the steel plant and another N310 million for its concession. In 2020, the government budgeted N4.2 billion for the plant.

The National Assembly, in 2019, approved N118.006 million as Export Expansion Grant for the complex.

Last Wednesday, the Transmission Commission of Nigeria disconnected Ajaokuta from the national grid as the moribund company failed to clear a debt of N33 billion owed to the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc (NBET) and service providers.

The N33 billion comprises N30.85 billion for energy and capacity delivered by NBET and N2.22 billion owed to service providers.

“It is a gradual process; Ajaokuta cannot be revived overnight. This is an institution, this is a plant that has not been working for 45 years, it is a difficult task to try and get it back on track,” Audu, minister of steel development, said last Thursday.

“So, we need the support of the entire government apparatus, we need the support of stakeholders, we need the support of everyone to be able to do this difficult job,” he added.