Deregulation in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector may not bring down the price of petrol unless the naira regains its value and global oil prices fall. Despite progress, full deregulation remains a distant goal.

The concept of deregulation in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector is far from new. According to a paper by Funsho Kupolokun, former Group Managing Director of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), deregulation dates back to 1965. In 2004, during a presentation to the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Kupolokun highlighted how deregulation enabled NNPC to issue 18 licences to prospective investors, with five approved for construction.

“For a true market-driven system, the price of petroleum would move with the global oil market. Yet, as long as the naira remains volatile and weak, the impact of global oil price changes will not benefit Nigerian consumers.”

This raises a question: is today’s deregulation any different from the reforms of the past? For instance, the deregulation of the early 2000s, through the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS), aimed to achieve self-sufficiency in refining and allow petroleum prices to be determined by market forces. It also encouraged marketers to source products both locally and internationally.

Fast forward to the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021, which promised similar benefits—creating a more competitive oil and gas sector and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). However, it seems we’re still on the journey to full deregulation.

Is Nigeria fully deregulated?

In a recent interview, Akin Ogunsola, an economist, responded to claims that Nigeria has fully deregulated its oil and gas sector, saying, “I’m not sure we have total deregulation yet.” According to him, “if we had total deregulation, we wouldn’t be discussing whether Dangote Refinery is supplying enough petrol to the Nigerian market.”

He further noted that NNPC is still importing a significant portion of petroleum products to the country—a clear sign that Nigeria is not fully deregulated. This reality clashes with the government’s statement on October 11, 2024, which announced the full operation of a deregulated market.

The government’s statement claimed: “With this mechanism now in full operation, along with the commencement of local production, we are well-positioned to transition to a fully deregulated market for all petroleum products.” Yet, as Ogunsola pointed out, market forces are still not the sole determinant of petrol prices, and there is the likelihood of further price increases.

Read also: Nigeria begins oil deregulation: A shift toward market forces

Exchange rates and global oil prices: the key variables

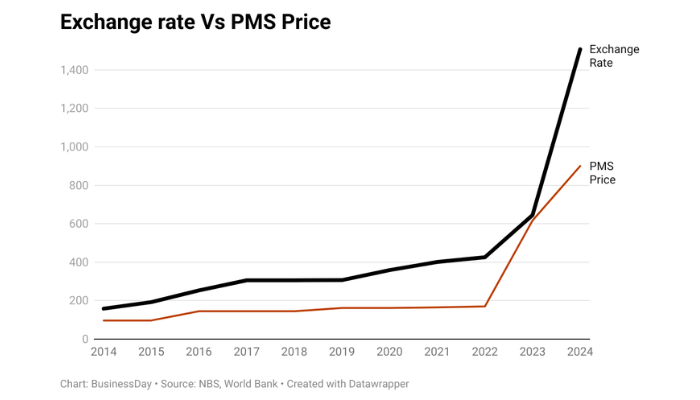

If Nigeria were fully deregulated, the price of petrol would fluctuate based on two main factors: the exchange rate and the global oil price. The unfortunate reality is that, after many years of attempted reforms, the naira continues to depreciate, and petrol prices have not fallen in tandem with global oil prices when they drop.

For a true market-driven system, the price of petroleum would move with the global oil market. Yet, as long as the naira remains volatile and weak, the impact of global oil price changes will not benefit Nigerian consumers.

The ongoing tension between Dangote Refinery, NNPC, and fuel marketers reflects this imbalance. Aliko Dangote stated that his refinery has enough crude supply and can produce over 30 million litres of gasoline daily, exceeding domestic demand. Yet, NNPC and marketers continue to favour imports. This suggests lingering control and intervention in the supposedly deregulated market.

The volatility of the exchange rate

Economist Kelvin Emmanuel emphasised that petrol prices are largely determined by the price of crude oil and the exchange rate. “We have a volatile exchange rate in the country,” he stated, pointing to the uncertainty this creates in the market.

While recent meetings between President Bola Tinubu and stakeholders like Dangote discussed the possibility of selling crude in naira, Emmanuel argued that this would have limited impact if the government cannot guarantee a steady supply of 400,000 barrels of crude per day to Dangote Refinery and stabilise the exchange rate.

Ayo Teriba, the CEO of Economic Associates (EA), blamed the exchange rate volatility on Nigeria’s low foreign reserves, warning that inadequate reserves lead to capital volatility and further exchange rate swings.

Is full deregulation feasible?

It’s clear that deregulation is still a work in progress, and the full benefits are yet to materialise. Prices may rise further if global oil prices increase or the naira continues its slide. More importantly, the sector may never be fully deregulated, as government intervention could remain necessary due to the developmental needs of the Nigerian economy.

As my colleague Oluwatobi Ojabello recommended in a recent article titled Nigeria Begins Oil Deregulation: A Shift toward Market Forces, Nigeria might benefit from exploring Kenya’s price modulation strategy or South Africa’s fuel pricing formula. These models could offer insights into balancing market-driven policies with regulatory oversight to ensure the sector’s stability.