A chief economist at Shell once described Nigeria as the “jewel in the crown” of the oil major’s empire. Yet in recent years, the jewel has lost its lustre.

Early this year, Shell, which has been pumping oil in Nigeria for nearly seven decades, agreed to sell its onshore subsidiary to a consortium of mostly local companies.

Gbenga Komolafe, chief executive of the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), surprised many in the industry on October 21 by saying the sale to a local consortium, Renaissance Africa Energy, was blocked because the transaction did “not scale [the] regulatory test.”

While he did not provide details of the regulator’s reasoning, experts said this development, while disappointing for some, offers a stark reminder of the complex issues hindering Nigeria’s potential to maximise its oil wealth.

“Nigeria has had well-established problems in policy in the oil sector, and the foreign exchange policy concerns have put constraints on investments. That’s probably partially why you have seen the majors pulling out, and disinvesting to some extent,” Andrew Matheny, senior economist with Goldman Sachs, told Reuters.

Matheny added, “It explains a significant portion of the decline in oil production in recent years.”

Read also: NUPRC rejects Shell’s $1.3bn onshore asset sale to Renaissance

Twenty-one years ago, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC) share of production was as high as over one million barrels of oil per day (bpd) in Nigeria.

This fell to 290,000 bpd in 2023, which the company blamed on sabotage and theft in the Niger Delta, its annual reports showed.

Analysts said basic economics should ordinarily nudge Nigeria towards a deal Shell said it has structured to maintain SPDC operational capabilities to support the SPDC Joint Venture (SPDC JV).

Data sourced from Shell Nigeria’s Briefing Notes 2023 showed that SPDC JV’s operating assets include: 250 producing oil wells (189 West assets and 61 East assets), 37 producing gas wells (4 West assets and 33 East assets), four gas plants, and two onshore oil export terminals.

As part of the transition, SPDC’s employees will remain with the company under the new ownership.

“It is time we tried a more viable approach, which is to allow the independents with trackable records to play a significant role in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector,” a business leader in the upstream sector said during an interview in his Lagos office.

Read also: Boon for Nigeria as Shell’s $1.3bn assets sale gets regulatory nod

Indigenous Nigerian oil producers currently pump about 10 percent of national output and have invested billions of dollars in the past 10 years to position themselves for growth and to play a bigger role in the sector dominated by International Oil Companies (IOCs).

There are at least 50 small to mid-sized Nigerian producers pumping between 1,000 and 100,000 barrels each day.

Some local firms, including Seplat, First E&P and Heritage, have managed to raise production and reduce oil spills on assets purchased from Shell.

BusinessDay’s findings showed the Renaissance consortium comprises some of Nigeria’s most respected upstream companies such as ND Western, Aradel Energy, First E&P, and Waltersmith, all local oil exploration and production companies with demonstrated track records of redeveloping mature assets in the Niger Delta.

Individually, each of Renaissance’s shareholders has also demonstrated an ability to operate in Nigeria and maximise domestic value creation. Aradel Holdings has grown an integrated oil, gas and refining business around Ogbele that has continued to expand over the years.

Waltersmith follows a similar pattern as the operator of the producing Ibigwe marginal field and the Ibigwe modular refinery.

First E&P successfully commissioned the Anyala-Madu shallow water hub in 2020 and is working with Dangote on achieving the first oil at the Kalaekule Field soon.

“These local oil companies have operated in the difficult terrain and environment that is the onshore Niger Delta,” Bello Rabiu, an independent energy consultant based in London, said.

For years the Delta has been plagued by kidnappers, thieves, saboteurs and collapsing infrastructure. Operating there, the majors argue, is simply not worth the risk.

The wave of divestments is giving rise to anxiety in Nigeria that its most vital industry is in terminal decline. For decades Nigeria has been Africa’s biggest oil exporter. Yet production has slumped by nearly 50 percent from its peak in 2005 because of insecurity onshore and higher costs offshore.

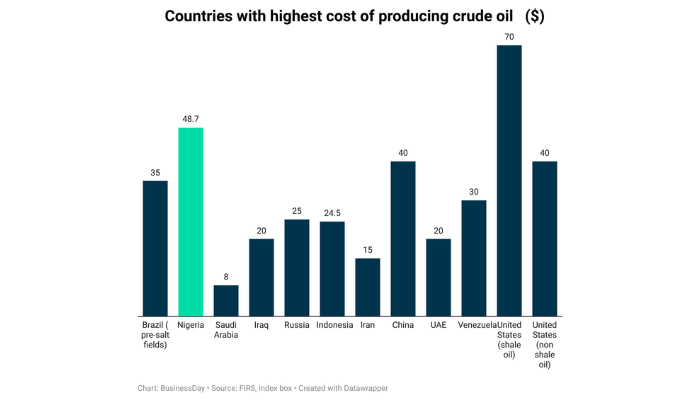

In theory, getting a barrel of Nigerian oil out of the ground should cost about $15 on average, according to Rystad Energy, a consultancy. But that is not the case. Insecurity in the Delta has driven up costs and pushed investment into offshore waters, where production costs are higher. As a result, it costs $48 to pump a barrel of oil in Nigeria.

This means it’s much cheaper to produce crude oil in war-torn Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Iran than in Nigeria, Africa’s biggest oil producer.

Findings showed most oil companies have set aside massive budgets for the security of assets, settlement of community troubles, and multiple taxation, among others.

“While the impact of the security challenges in terms of oil production is being talked about at the highest levels, another part seldomly discussed is the wave of impact on companies who are now required to spend more on the protection of workers and oil facilities,” Chinedu Onyeka, an energy sector expert familiar with upstream business, said.